Body and Bore

The Bore "is the instrument" (well, nearly)

The bore is the cylindrical hole in the clarinet's body from the bottom end of the mouthpiece to the top of the bell (the funnel-shaped part). The clarinet player usually does not pay much attention to bore although it is the part of the clarinet that sounds - that is: the air column in it swings which produces the sound. The mouthpiece with the reed just causes the vibration of the air column, but the air column itself and thus its properties are defined mainly by the bore.

Qualities of the bore

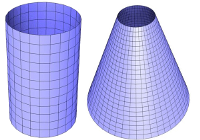

As said above, the bore is pretty much cylindrical so it has the same diameter all along the instrument (the graphic left compares cylindrical and conical). In the first clarinets and in today's German systems, it is nearly perfectly cylindrical while in the Boehm systems it widens and narrows in some places to improve intonation. This cylindrical bore determines the acoustical behavior of the vibrating air column inside. The clarinet is a member of the instrument family of pipes - this family also has flutes and organs as members. Most other wind instruments have a bore that - starting at a very slim mouthpiece - gets wider and wider. This is true for the oboe, the bassoon, saxophone and most traditional brass instruments. This, too, is the main difference between clarinet and saxophone: The saxophone is NOT a metal clarinet, it is acoustically something completely different - it is rather a very fat oboe (with a bore that is about 5 times wider) that has a clarinet mouthpiece attached. The fact that a saxophone is usually made of metal does not mean much since there also are clarinets that are made of metal.

The diameter of the clarinet bore is usually 15 mm (14.7 -- 15.2) with B flat clarinets. This diameter is standardised which makes it possible to use mouthpieces by different manufacturers.

What happens in the bore when you play?

The air actually streams into the bore and pressure waves within the bore go through the bore starting from the mouthpiece to the opening of the bell and back (you find a more detailed description in the sound chapter).

To support this optimally the bore should be completely smooth and nothing should hinder the flow of air and pressure waves. If you put the clarinet parts together and look through it against a light, you should see one single, shiny, completely smooth pipe through which air and waves can travel without resistance and therefore stream without whirls. But of course this is not fully so: The key holes interrupt the bore wall and may produce whirls. Then many clarinets have a small pipe at the register key which sticks right into the bore (can be seen well on the picture above). This is necessary, because this hole is the only one on the back side of the instrument and therefore, when playing, on the bottom side. All water, like saliva and condense water, would flow into the hole without the pipe - but it is not a good thing for the acoustic. Therefore new designs overcome this problem by applying a wraparound key. And, of course, it also has consequences if an otherwise perfect bore is interrupted by pulling out the barrel in order to "tune" the instrument.

Problems with humidity in the bore - application of instrument oil

So the bore in which the tone vibration takes place is a drilled and polished hole in wood. Unfortunately, a lot of things happen to this wood that will have a negative effect on the bore: From being rather cool when you take the instrument out of the case (like 10°C in winter) the inner surface soon will be warming up quickly to about 30°C. Add to this the humidity of your breath and a fine saliva fog which will cover the upper part of the bore - while the lower part is still cold and dry. Condensing water builds up and eventually might run down the bore. Once little streams build up they will continue to take that same way that usually ends in a tone hole which will be filled with water - this produces gargling noises. To prevent this it is a good idea to regularly wipe through your instrument when playing. This requires that you can quickly remove the mouthpiece and set it back into exactly the same position.

Humidity and changing temperature are, of course, poison for every wood. At the moment there is only one known way to help: to impregnate wood by oiling it. This is done for the first time right after the parts are drilled practically ready. The oil is applied in tanks under pressure. It penetrates the wood and should take care that it becomes water repellent.

You can occasionally (like once a year) oil the instrument yourself or have it oiled. If you do it yourself, make sure that you do not leave a sticky oil/dust mixture in the tone holes. You find more thoughts about applying oil in this article.

Wipers

It appears advisable to use a leather wiper made from window wiping leather (cut into a slim triangle) and a sewed-on long string to wipe the bore of your instrument. The idea is that - as long as the leather is rather new - it will leave a small quantity of oil in the bore, too. You should avoid to use wipers made of hard fibre substances (such as silk and some - not all - microfibres - both are harder than steel!) because they can have a sanding effect, neither use fluffy materials that can leave dust particles in the bore or - to be avoided - in the tone holes. The really worst is the wire-soul/woollen wiper, because next to leaving dust and fibers in the bore the wire soul can also scratch the surface of the bore "... which probably is the reason why evil and cunning instrument dealers all over the world usually put one into every instrument case ..." ;-) as Jack Brymer writes in his book.